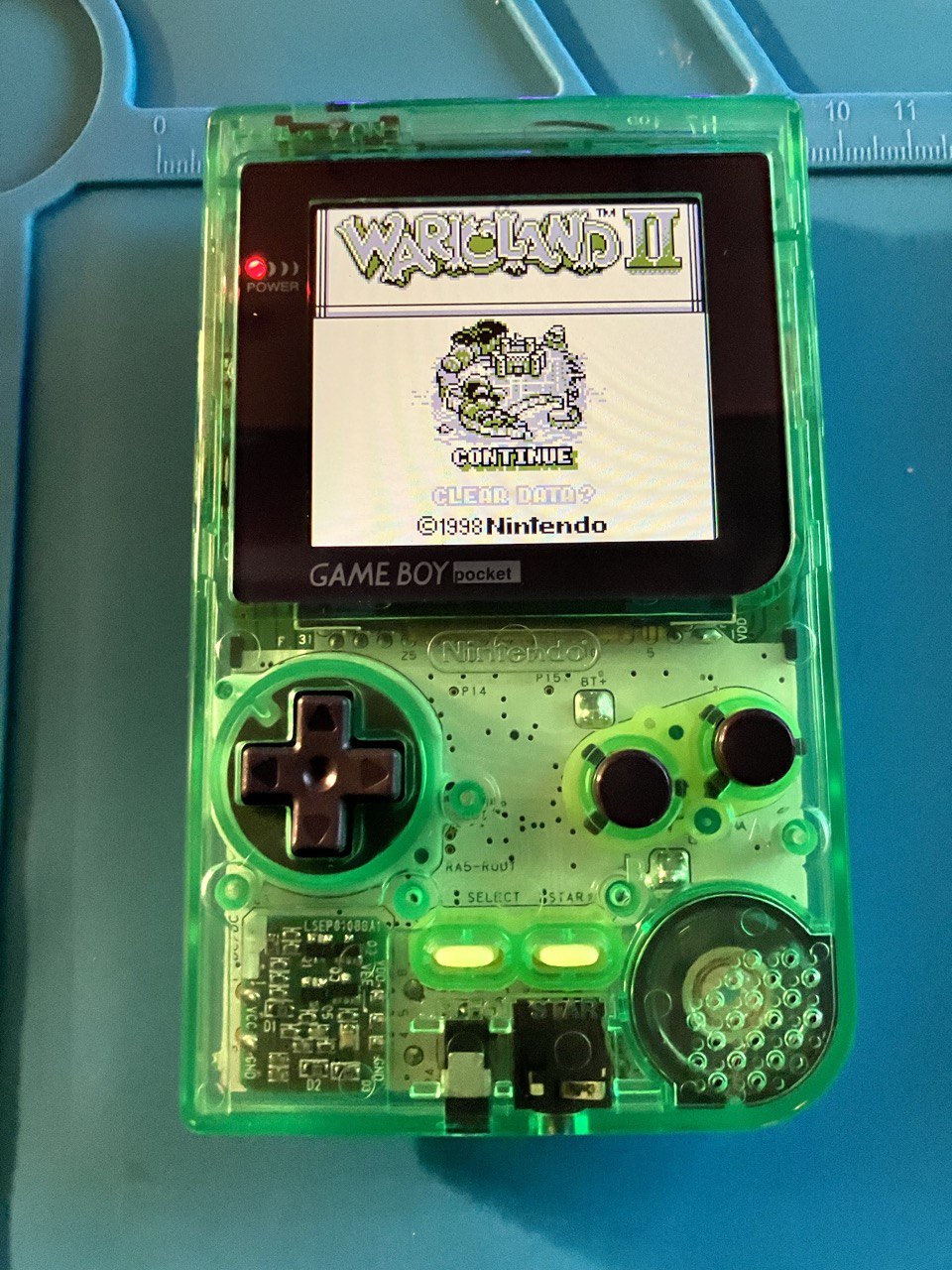

Aún recuerdo ese verano. Tenía 13 años, y alquilé un video juego con un amigo para la SEGA Megadrive que quedaría impreso en mi memoria (de hecho, aun recuerdo alguno de los cheat codes :-)).

El juego del que hablo es “Asterix y Obelix: El gran rescate”. No por el juego en sí, que a pesar de ser divertido, era bastante mediocre para la época, sino porque su banda sonora era muy elaborada, dinámica, y ganaba protagonismo sobre la acción del juego, cosa tampoco demasiado común, donde en general las bandas sonoras de 16 bits se acababan por hacer algo repetitivas tras unas cuantas horas de juego.

Con 12 o 13 años, no estaba muy puesto en compositores musicales, tampoco me cuestionaba asuntos relativos al juego, mucho más allá de cómo pasarme el nivel, pero gracias a una escucha adulta posterior, me he dado cuenta que la calidad de esta obra no es casualidad. Nathan McCree era la persona detrás de esta elaborada composición (luego vendrían cosas como Tomb Raider). Pero aún así, me pregunto: con las limitaciones de los medios de la época, ¿cómo fue posible alcanzar ese nivel de sofisticación?

Por su puesto, me estoy refiriendo a usar un chip como instrumento, y una interfaz de texto como entrada, para alguien, que incluso siendo compositor musical, tuviera unas restricciones tan marcadas. Otro claro ejemplo de esta asimetría, y que me recordó un amigo el otro día, es “Monty on the Run”, con un Rob Hubbard quasi barroco:

En el caso de Megadrive el chip era el YM2612, fabricado por Yamaha. Lo curioso de este procesador: limitado en cuanto a reproducción de samples de audio:

While high-end chips in the OPN series have dedicated ADPCM channels for playing sampled audio (e.g. YM2608 and YM2610), the YM2612 does not. However, its sixth channel can act as a basic PCM channel by means of the ‘DAC Enable’ register, disabling FM output for that channel but allowing it to play 8-bit pulse-code modulation sound samples.

y además había que controlar la frecuencia y el buffering en proceso principal:

Unlike other OPN chips with ADPCM support, the YM2612 does not provide any timing or buffering of samples, so all frequency control and buffering must be done in software by the host processor.

Para el caso del Commodore, el Sound Interface Device: SID

The majority of games produced for the Commodore 64 made use of the SID chip, with sounds ranging from simple clicks and beeps to complex musical extravaganzas or even entire digital audio tracks. Due to the technical mastery required to implement music on the chip, and its versatile features compared to other sound chips of the era, composers for the Commodore 64 have described the SID as a musical instrument in its own right.[15] Most software did not use the full capabilities of SID, however, because the incorrect published specifications caused programmers to only use well-documented functionality. Some early software, by contrast, relied on the specifications, resulting in inaudible sound effects

Maldita sea, parece que en vez de componer, luchaban contra el instrumento. De alguna forma, esa limitación técnica (oh sorpresa!) dio lugar a decisiones brillantes.

La solución más evidente al oído es el uso intensivo de arpegios rápidos. ¿Que no podemos hacer acordes? No problemo, se simulan descomponiéndolos en sucesiones de notas individuales tocadas muy rápido. El oído humano hace el resto. En chips como el SID del Commodore 64, con solo tres voces disponibles, esta técnica permitía componer armonías complejas, con bajos y melodías simultáneamente.

Rob Hubbard fue un maestro en este arte. Monty on the Run no suena como un simple tema pegadizo: suena exuberante, casi excesivo me atrevería a decir, como si el chip estuviera a punto de explotar. Y, en cierto modo, lo estaba:

- Sonidos que aparecen y desaparecen en milisegundos

- Timbres que mutan mientras la nota sigue sonando

- Una polifonía aparente casi imposible

Y mirando las rutinas musicales desensambladas, vemos:

- Rutinas de interrupción extremadamente ajustadas

- Cambios de registros del SID dentro del mismo frame

- Uso deliberado de valores ilegales o mal documentados

- Escritura en registros en momentos muy concretos del raster

Nathan McCree jugó una partida distinta pero igual de interesante en el caso de la Megadrive.

El YM2612, con la síntesis FM, permitía timbres más ricos que los PSG clásicos, pero imponía otra clase de “desventaja” (que en realidad no lo era): sonidos metálicos, bajos difíciles de controlar, y un DAC rudimentario. Aun así, McCree consiguió una banda sonora con estructura, leitmotivs y desarrollo, algo poco habitual en juegos de acción de la época.

Aquí aparece otro truco, creo, fascinante: usar el canal DAC no como un sampler tradicional, sino como textura para la percusión y el bajo. Los timbres, los golpes metálicos, casi “sucios”, cosas que hoy llamaríamos glitches, pero que entonces eran el resultado de empujar el chip más allá para llegar a imitar un sonido concreto. Ese ruido, casi analógico, le daba el carácter único.

Otros compositores siguieron caminos similares. Yuzo Koshiro, por ejemplo, en Streets of Rage, llevó el YM2612 a territorios casi underground, inspirándose en el house y techno de los 90’s, con patrones rítmicos que disimulaban las limitaciones del chip mediante la repetición hipnótica de melodías muy pegadizas.

Y Tim Follin, por su parte, parecía directamente ignorar las reglas: sus composiciones para NES, Commodore o Spectrum sonaban imposibles, con esas escalas rápidas, modulaciones extremas y cambios de dinámica que ahora me hacen preguntarme si realmente salía de ese chip:

Y aquí es donde la asimetría se vuelve evidente: juegos modestos, incluso mediocres, sostenidos por obras musicales que los superaban. Como si alguien hubiera colgado un cuadro de un pintor flamenco en el salón de un piso de estudiantes.

Con el paso del tiempo, pienso que muchas de estas bandas sonoras han sobrevivido mejor que los propios juegos. Se reinterpretan en conciertos, se versionan, se analizan en vídeos técnicos:

Quizá porque, en el fondo, no eran solo música funcional: eran demostraciones de ingenio humano frente a la escasez. Arte nacido de la restricción.

Y tal vez por eso siguen fascinándonos. Porque nos recuerdan que la creatividad no florece cuando todo es posible, sino cuando casi nada lo es. Y digo esto habiendo usado IA en este largo ensayo. Que de otro modo, jamás hubiera escrito. What a time to be alive!